Volume II, Issue I

|

Heather Clayton, the author of Making the Standards Come Alive!, is the principal of Mendon Center Elementary School in Pittsford Central School District, New York. She is also a co-author of Creating a Culture for Learning published by Just ASK. Quotes That Inspire Questions

“Beggar that I am, I am even poor in thanks.” – Shakespeare “I have made this letter longer than usual, because I lack the time to make it short.” – Pascal “Lost time is never found again.” – Benjamin Franklin “To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield” – Alfred Lloyd Tennyson “That man is the richest whose pleasures are the cheapest.” – Henry David Thoreau “The cruelest lies are often told in silence.” – Robert Louis Stevenson “There is nothing I love as much as a good fight.” – Franklin Delano Roosevelt |

The Art of Questioning: The Student’s Role

“The whole art of teaching is only the art of awakening the natural curiosity of young minds for the purpose of satisfying it afterwards.”

– Anatole France

In order to successfully meet the expectations of the Common Core State Standards, students need to actively engage with the content they are learning. A powerful means for accomplishing this interaction is through the use of student-generated questions. In both English Language Arts and mathematics, students’ questions expand their thinking, promote reflection, clarify understanding, and require new ways of thinking about ideas, concepts, beliefs, opinions, problems, and solutions. Ultimately, student questioning helps students monitor their understanding and construct meaning.

For any text that they read or topics that they study, students have varying degrees of prior knowledge, connections, understanding, confusion, and misconceptions. By placing students’ queries at the center of the learning, not only do their questions personalize the learning and lend relevance, they motivate students to seek out answers from a variety of sources.

Students can, and should be, taught how to ask and answer their own questions. Naturally, when students have unanswered questions, they are driven to find answers and are curious about what they will discover. When this becomes a regular part of classroom practice, students will regularly ask meaningful questions to support their learning across all curricular areas. Rather than being passive observers they become active participants. It is also true that the more students learn and reveal, the more questions they have.

Keys to Teaching Students to Ask Meaningful Questions

Establish an environment where it is safe to ask questions

To quote E. E. Cummings, “Once we believe in ourselves, we can risk curiosity, wonder, spontaneous delight, or any experience that reveals the human spirit.” If teachers expect their students to risk in sharing their innermost thoughts, they need to ensure that the classroom is a safe place in which to do so. This can be done by modeling and expecting respectful listening, honoring students’ ideas, and creating multiple opportunities for students to actively engage in partner, small group, and whole group discussions. The classroom should be a place where all voices are heard and responses are free of judgment.

Promote student ownership of discussions

When instructing students, there is frequently a sense of urgency to convey essential information, and often the teacher’s voice becomes the primary one heard in the classroom. In order to promote student questioning and deep reflection, teachers need to be prepared to take a back seat. Their role becomes that of an active listener, and students are given time, space, and permission to let their wonderings and existing knowledge drive the conversation.

Model the process by thinking aloud

Students need a vision for what it looks like to ask meaningful questions in anticipation of or in response to the learning. One way to provide this vision, is for teachers to make their own questions visible for students by “thinking out loud.” When thinking aloud, it is important to know the material being presented well, and to pre-plan the questions that will be used for modeling. By doing so, teachers can ensure that questions have more than one possible answer and focus on the most essential to know information.

Betsy Blessington, elementary librarian, Pittsford Central School District, likes to use Marcus Pfister’s picture book Questions, Questions to model questioning. In his book, Pfister asks questions like:

- How do birds learn how to sing?

- When geese fly south, how do they know it’s time to leave

and where to go? - What makes fire burn red and gold and makes it much too hot to hold?

A middle school teacher models thinking aloud using the poem

|

|

Poemdown walls |

Think-Aloud Script“I’ve heard of income housing projects for poor people, often referred to as ‘the projects.’” (prior knowledge) “Safe” (key word from text) “I’m wondering how unsafe her life is outside of the elevator walls?” “Why is she/her family unable to ‘move up’ in their own lives?” |

Provide generic stems to help students get started

As students make the transition from learning to construct questions with the support of peers and their teacher to independently posing their own questions that help them clarify new learning, the use of question stems can be helpful.

- I wonder…?

- What if…?

- Why…?

- I don’t understand…

- It confused me…

- How can…?

- What did the author mean when he/she said _______?

- What do I know about this problem?

- What am I trying to find out?

- How will I solve it?

- Why will I choose to solve it this way?

Encourage the use of open-ended questions

Open-ended questions are those questions with more than one possible response, and that frequently include elaboration. In contrast, closed-ended questions, only require one word answers. As suggested in the book Make Just One Change: Teach Students to Ask Their Own Questions, a question that is open-ended often begins with words like why and how; closed-ended questions often start with do, can, and is. What, who, where, and when lend themselves to both open-ended and close-ended questions. Teachers should model open-ended questions to reinforce the use of questions that will lead to more learning and insight.

Middle School English Language Arts |

|

Sample Open-Ended Questions

|

Sample Closed-Ended Questions

|

Co-construct charts of student-generated questions

An important way to get students started asking their own meaningful questions, is to help them conceptualize what those questions should look like. As teachers explore different units of study, they should encourage students’ questions and chart students’ wonderings for all to see. These charts then become working documents throughout the unit, and serve as a place to verify questions that have been answered, add new questions as learning has occurred, and highlight those questions that students need more time to ponder.

Student Questions in Response to a Math ProblemA local musician comes to your school to give a performance in the gym. The gym is arranged with chairs so that the 150 members of your grade are all seated in rows. Each row contains the same number of chairs, and every chair is occupied. If 10 more chairs were added to each row, everyone could be seated in 4 fewer rows, allowing the back-row students to be closer to the performance. How many chairs are in each row in the original configuration? Our questions to help us solve the problem/clarify our thinking:

|

Teach students where to find the answers to their questions

When students pose questions, they generally look to their teacher for the answers. The goal, however, is for students to ask questions and to know where to search for the answers themselves. As students pose questions, there are likely places where answers can be found. Answers can be found:

- in the text they are reading or in the problem they are solving

- using clues from the text or the problem and what they know from prior knowledge and experiences

- through conversations with other readers and mathematicians

- using an additional source such as another text, an online resource, or an expert

Provide the time and means for students to seek answers

It is important that as students generate questions, that teachers do not let the process end there. The value in teaching children to be metacognitive, or to monitor their own thinking and understanding, comes from when they learn to think, reason, and propose their own answers to their questions. Teachers should be prepared to give students time to respond to their own wonderings, and to document the answers they have uncovered. To search out answers, students may talk in partners and groups in order to re-read texts or revisit solutions. Students can then capture their thinking in a simple bulleted list or on a questioning web, as illustrated in the examples below.

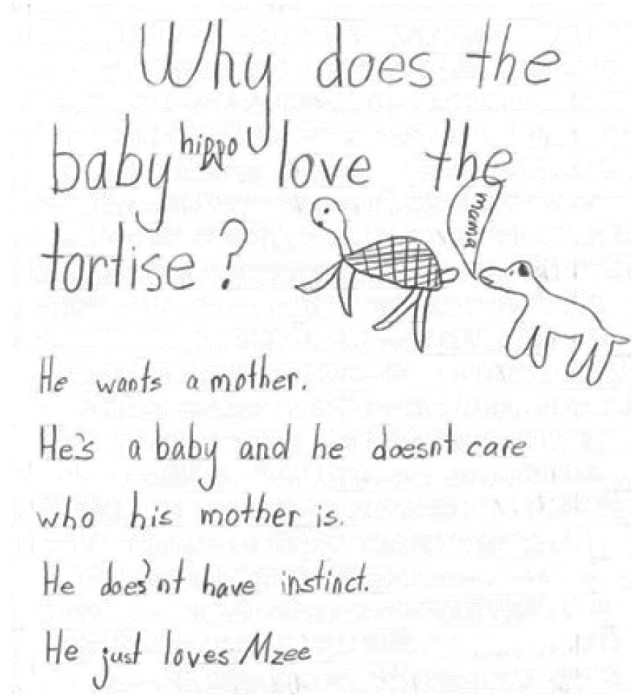

Student generated question and responses after reading Mama by Jeanette Winter |

|

After coloring in all of the multiplies of 3 and 6 on a hundreds chart, What do we notice about multiples of 3 and multiples of 6? Here is what they listed in response to their question:

|

Teach ways to help students organize their questions and thinking on paper

In their book, Strategies that Work, Teaching Comprehension for Understanding and Engagement, Stephanie Harvey and Anne Goudvis share a three-column graphic organizer with the headings Fact-Question-Response. In the fact column, students jot down important ideas they have taken from their reading. This framework could work for any genre, however it lends itself well to non-fiction, narrative non-fiction, and historical fiction. In the questions column, students write questions they have as a result of facts they jotted down in the fact column. Finally, in the response column, students respond to the facts and questions they wrote in the first two columns. Some starters to assist students in the response column could include “Perhaps…”, “Maybe…”, and “I’m thinking that…”

|

Expect students to have more questions as they acquire new learning

The more students learn through reading, problem solving, and talking, the more questions they should have. Not only should teachers expect those questions, but they should also have a plan for how they will honor those questions. As the Common Core expects, it’s important that our students know how to persist and seek to find the answers to difficult questions.

|

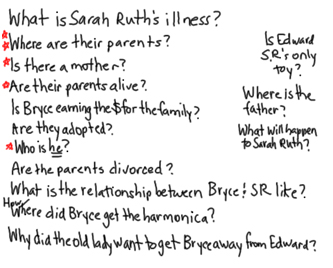

List of students’ questions during the reading of a chapter in The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane by Kate DiCamillo. The red stars represent questions that were common among several students.  |

After studying their list, students captured their thoughts in one “burning question.” They put it into a web in an attempt to find some answers.  |

In closing, we are teaching our students the habit of asking themselves meaningful questions when reading texts, solving problems, or becoming faced with new information. Students’ questions have an important role in learning no matter the subject area, age, ability, socioeconomic status, or gender of the child. By teaching our students how to question and reflect, we are reinforcing essential practices that will help prepare them for the future.

– Albert Einstein

Ways to Get Students QuestioningHave students generate questions about:

|

Resources and ReferencesClifton, Lucille. “Elevator.” Home: A Collaboration of Thirty Authors & Illustrators. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. DiCamillo, Kate. The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane. Somerville: Candlewick Press, 2006. Golenbock, Peter. Teammates. New York: Scholastic, 1990. Harvey, Stephanie and Anne Goudvis. Strategies that Work: Teaching Comprehension for Understanding and Engagement, Second Edition. Portland: Stenhouse Publishers, 2007. Pfeister, Marcus. Questions, Questions. United States: NorthSouth, 2011. Rothstein, Dan and Luz Santana. Make Just One Change: Teach Students to Ask Their Own Questions. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2011. Walsh, Jackie Acree and Elizabeth Dankert Sattes. Quality Questioning: Research Based Practice to Engage Every Learner. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press, 2004. Winter, Jeanette. Mama. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006. www.edutopia.org/blog/build-curiosity-questioning-strategies-kevin-washburn https://hepg.org/hel/article/507 |

Permission is granted for reprinting and distribution of this newsletter for non-commercial use only.

Please include the following citation on all copies:

Clayton, Heather. “The Art of Questioning: The Student’s Role.” Making the Common Core Come Alive! Volume II, IssueI, 2013. Available at www.justaskpublications.com. Reproduced with permission of Just ASK Publications & Professional Development (Just ASK). ©2013 by Just ASK. All rights reserved.