December 2018 Volume III Issue XI

|

Marcia Baldanza, the author of Professional Practices and a Just ASK Senior Consultant, lives in Arlington, Virginia. Until recently she worked for the School District of Palm Beach County, Florida, where she was an Area Director for School Reform and Accountability; prior to that she was Director of Federal and State Programs.

|

Creating a Culture of Inquiry:

A Focus on Data Teams

We’ve known for a long time that when teachers employ formative assessment in their classrooms, leaps in student learning take place. Let’s consider James Popham’s 2008 definition of formative assessment as a planned process in which evidence of students’ learning is used by teachers to adjust their ongoing instructional procedures and by students to adjust their learning strategies. However, even with our decades of knowledge, formative assessments remains inconsistently used in our classrooms. Ask a group of teachers from the same school or who teach the same grade or subject about their use of formative assessments. I’m certain their responses will vary widely. Why is that? I believe it is a confluence of variables, that when combined, make a true data-driven teaching and learning environment tough to begin and even tougher to sustain. Some possible reasons for not having data-driven teaching and learning environments are:

- School leaders are not always skillful with the collection and analysis of formative assessment data and may be uncomfortable discussing strategies to improve future outcomes.

- Teachers feel pressure to get through the curriculum pacing guides leaving little time to revisit previously taught (not necessarily learned) standards.

- If the pacing guides don’t allow for the revisiting of those standards, what use is formatively assessing?

- Teachers are ill equipped to manage the scope of real-time formative assessment data collection and analysis, given all they are responsible for in a day.

- Other tasks take over the calendar causing the time needed for the rich conversations limited or nonexistent.

Robert Rothman said, “Formative assessment is like tasting the soup.” in his submission in Harvard’s Strategies for School Improvement titled, “(In)formative Assessments: New Tests and Activities Can Help Teachers Guide Student Leaning.” Think about that idea for a moment. While making a pot of soup, we taste it as it cooks to make sure it has the right amount of salt, not too much pepper, and that the vegetables are not overcooked. We do the same with teaching and learning, taking samples along the way to see what adjustments need to be made. In this issue, I ask that we learn from our decades of unlearned lessons, make data-driven instruction a top priority in 2019, and taste the soup!

In recent years, a district-level trend has been to implement principal data talks: sessions usually held monthly, with individual principals making formal presentations to their superintendents, or sometimes the full cabinet, focused on student data. I participated in several of these where around the table sat district staff who were able to shift resources to support principal’s requests. What would happen if this same practice were moved to the school level where the teachers presented data to the principal and school-based leadership team? How would student performance change if teachers were collecting and analyzing data knowing it would be presented, discussed, and acted upon? At the district-level, I know that when a school principal asked for assistance from a large group of decision makers using data as a driver, things happen quickly. Resources were reallocated; staff were assigned, and reassigned; and teamwork improved all around. Certainly, we can make things happen quickly in our own buildings and classrooms, can’t we?

The data talk strategy encourages principals to become more informed about different kinds of data in order to become comfortable discussing trends in specific academic subject areas, especially mathematics and language arts, qualitative data for less numeric data, and to report accurately on the status of our equity efforts for closing the achievement gaps that remain among subgroups. More importantly, regular data talks have caused principals to become increasingly knowledgeable about classroom practices, since the point of the data talks is to hasten improvement.

To increase their own knowledge and expertise, many principals I know have increased the frequency of classroom walk-throughs, and have made these visits more focused on specific teacher practices (for example, checking for understanding). This has helped them clarify their expectations for teachers and provide more targeted and usable feedback.

Having a culture of inquiry means having people within a district or a school who regularly ask questions about what all students should know and be able to do, how best to teach content and skills, and what student demonstrations will be acceptable ways to measure learning. This idea illustrated in the Just ASK SBE Planning Ovals pictured below. This is my go-to tool to guide discussion about standards, curriculum, instruction, assessment and the use of student work to inform decisions.

Establishing and maintaining a culture of inquiry is important for optimal functioning of the data team; the data team also helps establish and maintain a culture of inquiry. So, which comes first? That’s hard to determine. So, I say just get started with the data team! Take some time this winter break to establish or re-establish your data team – either a district data team or a school data team. The references and resources section contains some compelling articles, texts, and tools to help you get started. This issue of Professional Practices has tips and ideas gleaned from my 25 plus years of leadership experience and practical research on school improvement.

An essential first step in creating a data-based culture is to understand the current perceptions about using data in your district or school. A teacher data use self-assessment can be informative as you begin your new team or press restart on your current team. Such a tool can help teachers understand what effective data use is and where they find themselves along the continuum.

Access this tool on the Instructional Leadership Resources page.

Access this tool on the Instructional Leadership Resources page.

Getting Started with Your Data Team

Build Your Team and Teacher Leadership to Boot

Building teacher leadership that is a natural outgrowth of the happenings in the classroom helps fill leadership pipelines. Often principals identify tasks for budding leaders to do to meet internship requirements or to ease a full principal plate. I’d like to make a case for establishing a data coach who is a teacher. What better way to build the pipeline and ameliorate some of the above reasons for not having data talks than to share this authentic and important activity? The data coach can be offered a monthly substitute day to fulfill the duties or given some other “payment” that shows the importance of the role. I also recommend offering the role to the entire school and holding interviews. You might use a case study as the interview, since much of the work of the data coach is of that type. You can build your own case study or find some online that can target data analysis, team collaboration, dealing with conflict, building trust, identifying appropriate strategies, etc. The benefit of offering the role to the whole school and holding interviews is that there just might be someone you don’t know well with the right attitude, skills, and knowledge (ASK). It also eliminates the perception that the person for the role is already known before the selection allowing everyone a fair shot. In the end the decision is yours and will be met with support if the process is deemed fair and open.

Start Small and Keep a Narrow Focus at First

As with any change that is a dramatic departure from past practice, it is best to start small, such as focusing on just one subject area. While the ideal teacher data talk would surface the same kind of data and issues as a principal data talk, teachers may not be prepared for the same scope of discussion principals engage in with district leaders. Principal support, encouragement, and participation is critical. Try using the tools at the end of this newsletter as a starting place to gain insight into student’s successes and failures and what you can do about them.

Connect the Dots Between the Data and Instructional Practices

Help teachers see how their practices influence student outcomes by helping them connect the dots between their classroom data such as grades, benchmarks, tests, quizzes, and informal measures of daily performance and their instructional practices.

Aligning these data talks with school-wide professional development, and teacher collaboration within grade levels or course-alike teams, is a powerful formula for making gains that any principal will be proud to report at the next principal data talk, and for improving student learning at any school, whether or not principal data talks are part of the driving force behind them.

Making Data Talks Work

I have been fortunate to have worked in progressive forward-thinking districts in Syracuse, New York; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Dallas and Houston, Texas; Atlanta, Georgia; Alexandria City Schools, Virginia; as well as Broward and Palm Beach Counties, Florida. Here are a few thoughts that have been shared with me over the years and that I have shared with teachers, instructional leaders, and principals during data talks.

When possible ask teachers to predict what data will show. This strategy increases the quantity and quality of questions emerging from a data review. When differences exist between predictions and data results, rich questions emerge. Questions are the ingredient that leads a data talk to critical thinking and the design of a plan for action to generate a desired student learning outcome. Action is crucial for teachers to find value in working with data. Absent action, teachers give up on formative assessments.

Limit the amount of data with which teachers are working. In many schools, teachers spend too much time collecting and/or examining too much data. In these cases, they rarely get to action. That lack of action leads to great frustration. Instructional leaders should work with teachers to select the most important data to support decisions about crucial areas of student learning. The school improvement plan probably helps identify where to begin.

Teachers need to trust the data and the people with whom they are working. I have been in data meetings where teachers are expressing doubt in the accuracy of the data in identifying students’ learning achievement. My first response is to encourage teachers to gather assessment documents from their classrooms that illustrate “why they doubt” and share that with their colleagues for study. Leaders need to build trust in the data to gain teachers investment in the process. Further, leaders must not allow excuses for poor performance and in some cases the expression of doubt might be an excuse.

Data produces questions not answers and can be used to tell a story. A Data Wall should become a Questions Wall. Use Data Walls to organize and understand data and to discuss with other teachers what the data show, set goals, and identify problems of practice. Data Walls should not be used to rank teacher or students, humiliate or embarrass anyone. Making data visible while preserving collegiality is a delicate act that requires a professional learning community built on trust, benevolence, support, and keeping your word as the leader.

Slow down to speed up by studying student work samples as well as data. My experiences are that teachers move to action more readily from conversations around student work samples. Sometimes, however, they can rush to a conclusion. Use student artifacts to collaborate with others to improve teaching practice and discuss work quality against a standard. Don’t rush this process. The conversation is important and often leads to better actions.

Be a champion for and of data. The most effective school data teams have members who want to support the inquiry process through the use of data and are broadly representative of staff and programs. Most states and districts have an adopted data use protocol or process. If your district doesn’t, there are several processes and protocols that when implemented with fidelity, can lead to improved outcomes for students. You can access an amazing array of protocols and processes in Heather Clayton’s Making the Standards Come Alive! newsletter issue titled “Norms and Protocols: The Backbone of Learning Teams.”

Be alert for potential potholes along the way. Debra Ingram and others uncovered seven barriers to the use of data to improve practice. Your team may encounter some of these and it’s useful to keep them in mind as well as developing a repertoire of responses to them when momentum stalls.

- Cultural Barriers

- Many teachers have developed their own personal metric for judging the effectiveness of their teaching, and often this metric differs from the metrics of external parties (e.g., state accountability systems and school boards).

- Many teachers and administrators base their decisions on experience, intuition, and anecdotal information (professional judgment), rather than on information that is collected systematically.

- There is little agreement among stakeholders about which student outcomes are most important and what kinds of data are meaningful.

- Technical Barriers

- Some teachers disassociate their own performance and that of students, which leads them to overlook useful data.

- Data that teachers want about what they consider to be really important outcomes are rarely available and usually hard to measure.

- Schools rarely provide the time needed to collect and analyze data.

- Political Barrier

Data have often been used politically, leading to mistrust of data and data avoidance.

As with any high functioning team, data teams function best when they take deliberate actions to organize their work and to promote interpersonal relationships among team members. Just because a team has been formed doesn’t mean that the members will be able to work cooperatively toward the desired end. It takes deliberate action, hard work, and determination to produce an effective team.

Access these tools on the Instructional Leadership Resources page.

Access these tools on the Instructional Leadership Resources page.

Download more tools from Creating a Culture for Learning at www.justaskpublications.com/ccltemplates.

Resources and References

Brookhart, Susan. How to make Decisions with Different Kinds of Student Assessment Data. Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2016.

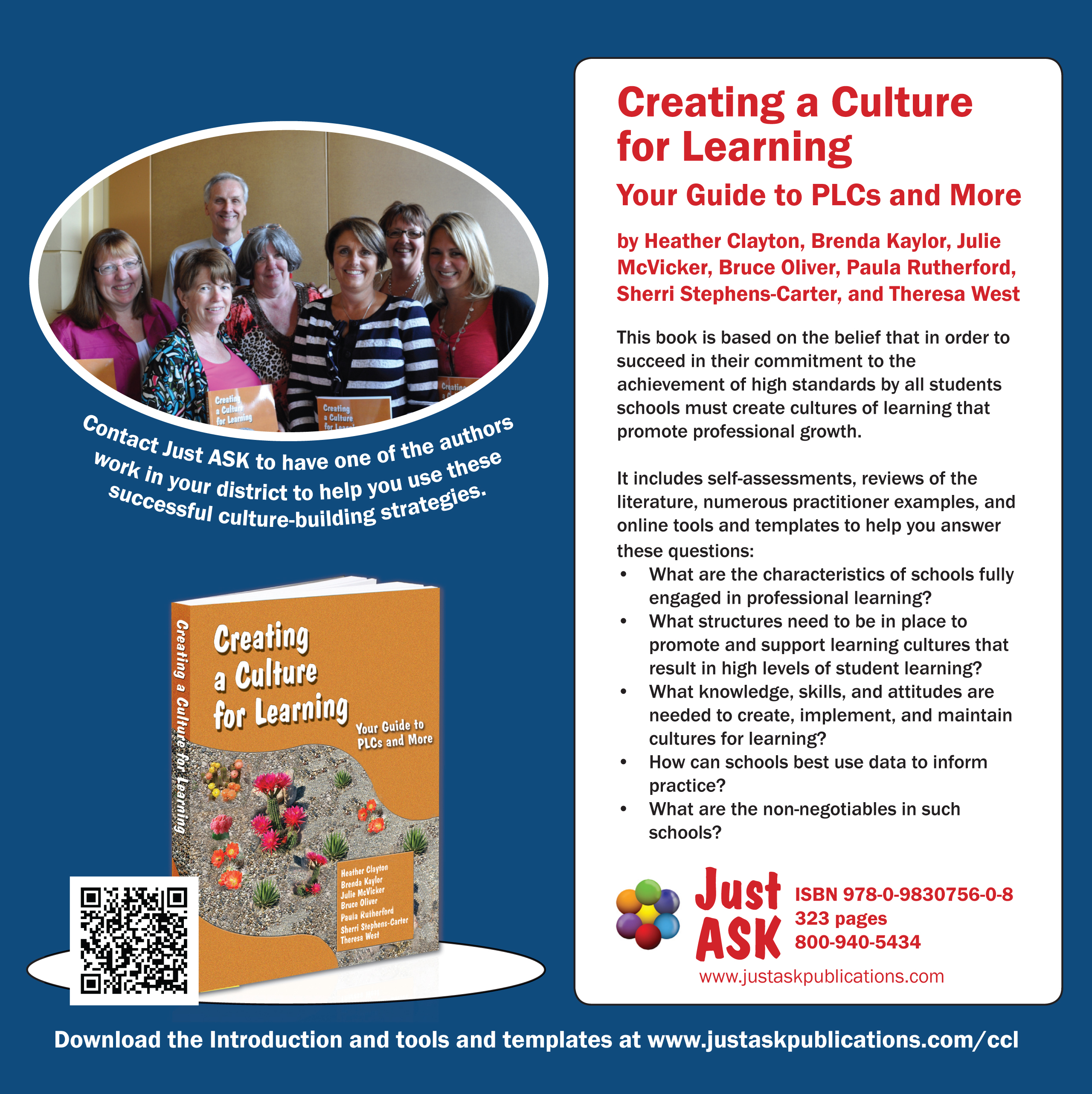

Clayton, Heather. et al. Creating a Culture for Learning: Your Guide for PLCs and More. Alexandria, VA: Just ASK, 2011.

Clayton, Heather. “Norms and Protocols: The Backbone of Learning Teams.” Making the Standards Come Alive! Alexandria, VA: Just ASK, 2015

www.justaskpublications.com/just-ask-resource-center/e-newsletters/msca/norms-and-protocols-the-backbone-of-learning-teams/.

Davenport, Patricia and Gerald Anderson. Closing the Achievement Gap. Houston, TX: APQC, 2002.

Geier, Robb and Stephen Smith. District and School Data Team Toolkit. Everett, WA: Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction, Washington School Information Processing Cooperative, and Public Consulting Group, 2012.

Ingram, Debra, Karen Seashore and Roger Schroeder. “Accountability Policies and Teacher Decision Making: Barriers to the Use of Data to Improve Practice,” New York City, NY: Teachers College Record, June 2004.

James-Ward, Cheryl, et al. Using Data to Focus Instructional Improvement. Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2013.

Love, Nancy, et al. The Data Coach’s Guide to Improving Learning for All Students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008. This is a great resource including tasks for the data coach to use, case study, and a CD-ROM and associated weblink to download materials and resources for the beginning and advanced data teams.

Mandinach, Ellen, et al. “Ethical and Appropriate Data Use Requires Data Literacy”, Phi Delta Kappan, February, 2015.

Murphy, Michael. Tools & Talk, Data, Conversation, and Action for Classroom and School Improvement. Oxford, OH: Learning Forward, 2009.

National Policy Board for Educational Administration. Professional Standards for Educational Leaders 2015. Reston, VA, 2015.

Parker Boudett. editor. Data Wise in Action: Stories of Schools Using Data to Improve Teaching and Learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2007.

Popham, James. Transformative Assessment. Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 2008.

Rothman, Robert. “(In)formative Assessment: New Tests and Activities Can Help Teachers Guide Student Learning. Strategies for School Improvement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2010.

This is No. 6 in the Harvard Education Letter Spotlight Series and is a compilation of 18 research articles by prominent and contemporary thinkers of school improvement.

Permission is granted for reprinting and distribution of this newsletter for non-commercial use only.

Please include the following citation on all copies:

Baldanza, Marcia. “Creating a Culture of Inquiry: A Focus on Data Teams.” Professional Practices, December 2018. Reproduced with permission of Just ASK Publications & Professional Development. © 2018 All rights reserved.